Riad is the product manager of Codecks. He is also the co-founder of indie games company Maschinen-Mensch and still believes that Street Fighter 2 is the most beautiful video game ever created. Coincidentally he also believes that Codecks is the best project management tool for game developers. Apparently he has been creating video games for over 14 years now and considers himself a productivity nerd: scrum, kanban, extreme programming, waterfall, seinfeld. He has tried it all.

Codecks is a project management tool inspired by collectible card games. Sounds interesting? Check out our homepage for more information.

A Scrum Guide for Game Devs: The Contract That Can Save Your Sanity

If you’re a game developer, chances are you’ve encountered Scrum. It’s probably the most popular development process framework used in our industry today. In pretty much every team I’ve worked in or heard from, Scrum, in one form or another, has been the go-to. But here’s the catch: also in every team, the actual process often ends up being something more like “Scrum-but…” – you know, mostly Scrum, but with a few rituals or roles conveniently skipped or modified. This is incredibly common.

So, what is Scrum really about, especially for us game devs? Is “Scrum-but” good enough? Or are we missing out on the core benefits by not understanding the original intent? I believe the fundamental power of Scrum lies in a simple idea: it’s a contract between the people doing the work and the people managing the work, designed to save everyone a lot of frustration and lead to better outcomes.

The Pain Points Scrum Tries to Solve: A Tale of Two Frustrations

Let’s be honest, the relationship between developers and management can sometimes be strained. I’ve certainly experienced this. Picture this: it’s Friday afternoon, and a manager drops by your desk. “Hey, great news! We have this super important, make-or-break demo for a stakeholder on Monday morning. We need you to build this new feature.”. Weekend plans? Gone, of course. That’s a drastic example, but it’s happened to me. More commonly, it’s the constant drip of shifting priorities, new “urgent” tasks appearing mid-week, and unrealistic deadlines that lead to stress, burnout, and a feeling that you can never truly focus and do your best work.

From the manager’s or stakeholder’s perspective, their frustrations are often the flip side: developers not finishing work on time, features being delivered with overlooked requirements, or the team focusing on isolated tasks instead of the bigger business goals.

The Scrum Contract: A Win-Win Proposition

Scrum attempts to solve these mutual pain points by creating a clear agreement, a contract, if you will.

- What Management (Stakeholders/Product Owner) Gets: They get to define the priorities: what’s the most important feature or goal for the next period of work (typically a “Sprint” of 1-4 weeks. We have a guide on how to plan a sprint specifically for game development). In return, they get a commitment from the development team to work towards achieving these goals with a focused, goal-driven mindset within that Sprint.

- What the Development Team Gets: They get a promise: for the duration of that Sprint, the agreed-upon priorities and goals will not suddenly change. No surprise tasks, no random shifts in direction. This allows them the stability and focus needed to actually get the committed work done to a high standard.

This is the core of the Scrum contract: clear priorities and commitment from management, leading to a protected period of focused work for the team, resulting in a valuable increment of the game. The various Scrum “rituals” or “events” are all built around establishing and maintaining this contract. When it works well, it’s a win-win, making development more comfortable and predictable for everyone.

A Quick Look Back: Where Did Scrum Come From?

Scrum isn’t just a random collection of meetings. It emerged as a specific framework under the broader “Agile” project management umbrella in the early 1990s. Its key architects were Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland. They drew inspiration from various sources, including a 1986 Harvard Business Review article, “The New New Product Development Game” by Takeuchi and Nonaka, which used the rugby term “scrum” to describe a holistic, team-based approach to product development.

Schwaber and Sutherland first formally co-presented Scrum at the OOPSLA (Object-Oriented Programming, Systems, Languages & Applications) conference in 1995. This presentation essentially documented the learnings they had gained over the previous few years working with teams. Later, both were among the 17 original signatories of the Manifesto for Agile Software Development in 2001. To further clarify and standardize the framework, they published the first official Scrum Guide in 2010, which has been periodically updated since then and remains the definitive source for understanding Scrum.

”Doing Scrum” vs. “Scrum-Inspired”: Why the Whole Package Matters

The creators of Scrum designed its roles, events, and artifacts to be an interwoven system, meaning each part reinforces the others. This means that, technically, to be “doing Scrum” by the book, a team should implement all of its core elements. If you’re only doing daily stand-ups and two-week sprints but skipping Sprint Reviews or Retrospectives, for example, then you’re not really doing Scrum; you’re using a “Scrum-inspired” process or adopting a few of its rituals. There’s nothing inherently wrong with a Scrum-inspired approach, but it’s important to understand what you might be losing by omitting certain pieces, as each is designed to uphold that central “contract.”

Codecks fits nicely into Scrum, too. We’ll also go through how each one of our features connects to Scrum, and how it can help.

Scrum Events & Artifacts in a Game Dev World (and how Codecks fits)

Let’s look at the key Scrum components and how they apply to making games:

1. The Product Backlog:

- What it is: A prioritized list of everything that might be needed in the game – features, art assets, mechanics, bug fixes, etc. The Product Owner is responsible for maintaining and prioritizing this.

- Game Dev Example: This could be a huge list of desired characters, levels, game modes, UI improvements, story elements, and player-reported bugs.

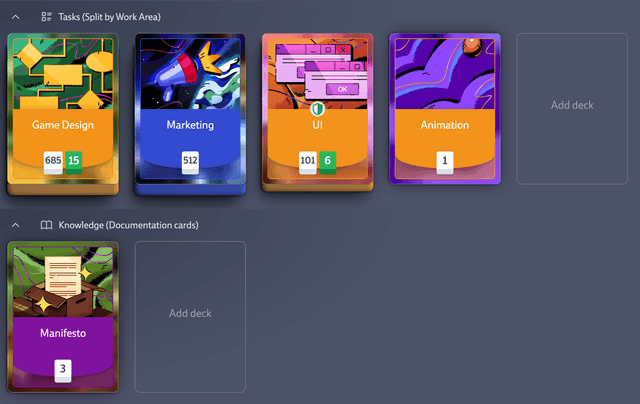

- Codecks Connection: In Codecks, your various Decks can serve as a living Product Backlog, where Cards represent individual backlog items. You can use Priority markers on cards and order them within decks to reflect their importance.

2. Sprint Planning:

- What it is: A meeting at the start of each Sprint where the team selects a realistic amount of work from the top of the Product Backlog to complete during that Sprint. This selection becomes the Sprint Backlog, and the team crafts a Sprint Goal.

- Game Dev Example: The team might pull in user stories like “As a player, I want to be able to control a new Mech type” or tasks like “Create 3 new enemy drone models” or “Implement the first pass of the new ‘Asteroid Field’ level.” The Sprint Goal could be “Deliver a playable prototype of the new Mech in one test environment.”

- Codecks Connection: Teams can create a Run in Codecks to represent their Sprint. During planning, they’d pull Cards from their main Decks (Product Backlog) into that specific Run. Estimating Effort on cards helps gauge capacity.

3. The Sprint:

- What it is: The fixed-length period (usually 1-4 weeks) during which the team works to complete the work in the Sprint Backlog and achieve the Sprint Goal. Critically, the Sprint Goal should remain stable during the Sprint (this is part of the “contract”!).

- Game Dev Example: A two-week period where the “Mech Squad” focuses solely on designing, modeling, animating, and coding the new Mech, aiming for that playable prototype.

- Codecks Connection: The Run view in Codecks provides a focused workspace for the current Sprint’s cards. Team members can update Card States (e.g., Unassigned, Assigned, Started, Review, Done) as they progress.

4. Daily Scrum (Stand-up):

- What it is: A short (typically 15-minute) daily meeting for the development team to synchronize activities and create a plan for the next 24 hours.

- Game Dev Example: The Mech Squad meets briefly to discuss progress on the Mech, any animation rig issues, coding roadblocks, or dependencies between artists and programmers. Each member might refer to their personal shortlist of tasks they intend to tackle.

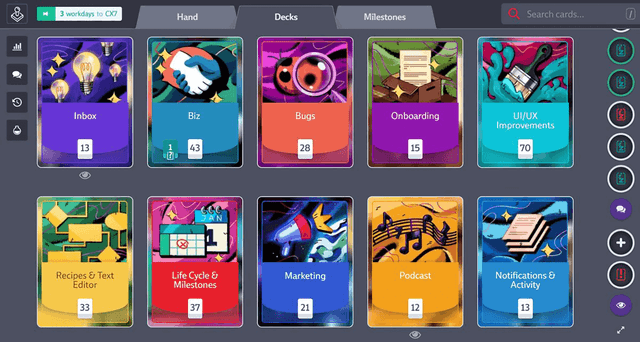

- Codecks Connection: The Codecks Hand feature can be very useful here, as it represents the short list of tasks each team member is planning to focus on next. Visualizing the Run in Codecks can also show overall progress and quickly highlight cards that are Blocked or ready for Review, informing the discussion.

5. Sprint Review:

- What it is: Held at the end of the Sprint to inspect the increment of the game that was built and adapt the Product Backlog if needed. The development team demonstrates what they accomplished during the Sprint to stakeholders. It’s a feedback session, not just a demo.

- Game Dev Example: The Mech Squad shows a live demo of the new Mech walking, shooting, and interacting in the test environment. Stakeholders (Product Owner, lead designer, publisher reps) provide feedback on its feel, functionality, and alignment with the game’s vision.

- Codecks Connection: The list of Cards marked as Done within the Run forms the basis of what’s reviewed. The internal Codecks Review process, which often precedes setting a card to Done, ensures that work has already been checked by team members. For teams using it, the Guardians feature in Codecks can further support this by ensuring designated people sign off on work related to specific topics before it’s considered truly ready for review.

6. Sprint Retrospective:

- What it is: An opportunity for the Scrum Team to inspect itself and create a plan for improvements to be enacted during the next Sprint. It focuses on the process, tools, and relationships within the team.

- Game Dev Example: The Mech Squad discusses what went well during the Sprint (e.g., “collaboration between art and code on the Mech’s VFX was great”), what could be improved (e.g., “we underestimated the complexity of the Mech’s transformation animation”), and what they will commit to trying differently next Sprint.

- Codecks Connection: The outcomes of a retrospective, like agreed-upon improvements or experiments, can be documented directly in Codecks using Doc Cards for detailed notes or Hero Cards to group related action items. These action items can then be tracked as regular Cards alongside other development tasks, ensuring they don’t get lost between different tools and are visible to the team. This is a big advantage of having a flexible, integrated system.

We’ve also written our A Step-by-Step Guide to Planning and Executing a Game Development Sprint, with a practical approach on how to set a sprint for you and your team.

The Elusive Scrum Master in Game Development

Scrum defines a specific role called the Scrum Master. Their job isn’t to manage the team in a traditional sense, but to act as a facilitator and a guardian of the Scrum process. They help the team understand and enact Scrum theory and practice, guide them through the events, help remove impediments, protect the team from outside disruptions (upholding that “contract” by shielding them from mid-sprint scope changes), and also hold the team accountable for achieving their Sprint Goals. Their work is often visible in the Daily Scrums by helping to uncover and resolve frictions slowing the team down.

You can even get certified as a Scrum Master. However, in many game development teams, especially smaller ones, having a dedicated, separate Scrum Master is rare. Often, this role is informally filled. A producer on the team can be a fine choice for this, as they are often already concerned with process and team efficiency. The main advice I have is to avoid having an active programmer or artist from the team simultaneously try to be the Scrum Master for that same team. If someone is both a “player” in the sprint (e.g., with their own coding or art tasks) and the “referee” (Scrum Master), they can face competing interests; for instance, prioritizing their own sprint tasks over helping unblock someone else, or hesitating to enforce a process rule that might affect their own work. A degree of separation, even if it’s a producer who isn’t directly contributing art or code to that specific sprint, can help maintain objectivity and better support the team in fulfilling their goals.

Conclusion: Scrum is a Tool, Use It Wisely

Scrum, when understood and implemented well, offers a powerful framework for navigating the complexities of game development project management, game development planning, and everything that goes into making a game. That “contract” it establishes (clear goals and protected focus in exchange for committed effort and valuable results) can genuinely save your team’s sanity and lead to better games.

However, simply adopting a few Scrum terms or holding a daily meeting isn’t enough. Its strength lies in the synergy of its roles, events, and artifacts. If you’re finding your “Scrum-but” implementation is leading to frustration, it might be worth revisiting the original Scrum Guide or resources like Mike Cohn’s “Succeeding with Agile” to understand the “why” behind each piece.

Whether you go full Scrum or adopt a tailored, Scrum-inspired approach, the key is to ensure your process truly supports your team in delivering value, communicating effectively, and adapting to the ever-shifting adventure that is making games.